The Label “Homosexual” and its Influence on the Reactions of Friends and Biographers of TE Lawrence to Accusations of Homosexuality – Part 1: Accusations

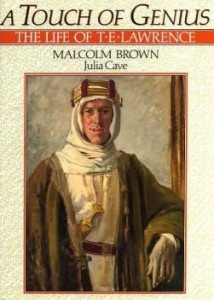

HOMOSEXUALITY AND ITS ROLE IN THE LIFE AND LEGEND OF TE

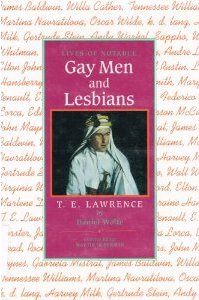

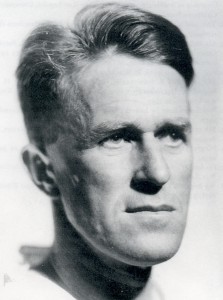

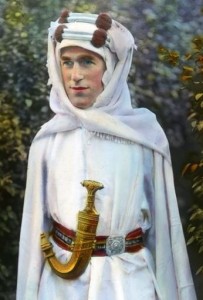

Was he homosexual or wasn’t he? It’s a question often asked about TE Lawrence. But it is not a question to which I will provide an answer here, for the simple reason that there is no convincing evidence to prove he was either a homosexual or to the contrary, that he was not. There are only a lot of suspicions and speculations for both positions, nothing more. Instead, I will deal with the label “homosexual”, the stereotype of evil and criminal behaviour that existed during TE’s lifetime and afterward, which forced friends and biographers to deal with this “unmentionable” subject. I will show that the arguments pro and con are not about homosexuality or the reality of TE’s life at all, but about proving or disproving evil and criminal behaviour, which was regarded as typical for homosexuals. Placing the heated and emotional discussion about TE’s homosexuality in the context of the views on the subject in his time will give a totally different perspective on a subject which still is very controversial in TE studies. This will be the first part of a series of articles on this blog, about manly love, homosexual behaviour and homosexuality, and the role they played in the life and legend of TE.

Was he homosexual or wasn’t he? It’s a question often asked about TE Lawrence. But it is not a question to which I will provide an answer here, for the simple reason that there is no convincing evidence to prove he was either a homosexual or to the contrary, that he was not. There are only a lot of suspicions and speculations for both positions, nothing more. Instead, I will deal with the label “homosexual”, the stereotype of evil and criminal behaviour that existed during TE’s lifetime and afterward, which forced friends and biographers to deal with this “unmentionable” subject. I will show that the arguments pro and con are not about homosexuality or the reality of TE’s life at all, but about proving or disproving evil and criminal behaviour, which was regarded as typical for homosexuals. Placing the heated and emotional discussion about TE’s homosexuality in the context of the views on the subject in his time will give a totally different perspective on a subject which still is very controversial in TE studies. This will be the first part of a series of articles on this blog, about manly love, homosexual behaviour and homosexuality, and the role they played in the life and legend of TE.

THE LABEL “HOMOSEXUAL”

The picture of homosexuality which emerges from the studies and biographies of TE is simply astonishing. A homosexual is not a very nice chap. He is a pathologue and a pervert, who indulges in secret vice. Having an unhappy twist, he is indelicate, indecent, coarse, unclean, and physically and morally deformed. His behaviour is improper, making smutty remarks and having queer friends. Fortunately he is easy to recognize, because he displays mannerisms consistent with particular physiological traits, such as having wide hips. A homosexual hates women, and makes difficulties with the wives of his friends. Women are not attracted to him sexually in any way, and therefore marriage is out of the question. When living intimately together with groups of men, a homosexual is incapable of hiding his sexuality, and therefore he cannot have heterosexuals as tent- or room-mates. Still they are relatively safe from his perversion, since a homosexual can only have sex with other homosexuals, otherwise it would be no fun. (*1) Staggering as this may sound, these views are typical of the norms and values that were dominant in the society of TE’s time.

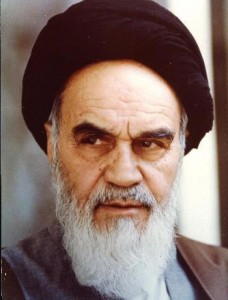

Homosexuals were different from the norm, and their otherness was perceived as being suspicious, dangerous and evil. They were considered to be a danger to society and consequently criminalized for their dreadful homosexual behaviour (“sodomy”). Applying the label “homosexual” (and later “gay”) to an individual “in these circumstances is not necessarily a reflection of their actual sexuality or sexual conduct, but upon the perceived state of their character; it is a label used to discredit and to confirm that the exclusion is deserved.” (*2) It was not just that homosexuals were bad people themselves, it was also the other way around: bad people had to be homosexual. It’s an old tradition which goes back to the Egyptians, Greeks and Persians, to consider the enemy to be effeminate. Consequently both enemy men and women were often raped, to prove the point. And we still find it in modern times, like for example in the executions of homosexuals in Iran during the revolutionary period of the eighties, when Ayatollah Khomeiny took over.

HOMOSEXUALITY AS EVIL: THE EXAMPLE OF IRAN

Between 1979 and 1984 there was a lot of outrage in the Western media about executions of homosexuals in Iran. After thorough investigation, however, it turned out that most of the people involved were not homosexual at all. They were murderers, rapists and drug smugglers, and since they were considered to be bad people already, they were labelled by the authorities in Iran to be homosexual too. The term “homosexual” was used as a negative label, referring to behaviour which clashed with the God-given order of society and with the social role pattern. It violated public decency, and was regarded as a typical example of the shameless and depraved decadence of Western society, whose permissiveness made license public, which would ultimately led to social chaos. “Homosexual” referred specifically to passive homosexual behaviour, which was considered particularly objectionable, because it topsy-turvied God’s creation, and threatened the God-given harmony between men and women, which is reflected in the social role pattern. And finally, it also referred to the public transgression of morals, the conscious refusal to hide behind the veil of secrecy, and thus openly challenging established norms and values. As in the story of Lot (and the people of Sodom and Gomorrah), homosexual behaviour had become symptomatic of evil behaviour in general. It would inevitably lead to chaos and decay,

Between 1979 and 1984 there was a lot of outrage in the Western media about executions of homosexuals in Iran. After thorough investigation, however, it turned out that most of the people involved were not homosexual at all. They were murderers, rapists and drug smugglers, and since they were considered to be bad people already, they were labelled by the authorities in Iran to be homosexual too. The term “homosexual” was used as a negative label, referring to behaviour which clashed with the God-given order of society and with the social role pattern. It violated public decency, and was regarded as a typical example of the shameless and depraved decadence of Western society, whose permissiveness made license public, which would ultimately led to social chaos. “Homosexual” referred specifically to passive homosexual behaviour, which was considered particularly objectionable, because it topsy-turvied God’s creation, and threatened the God-given harmony between men and women, which is reflected in the social role pattern. And finally, it also referred to the public transgression of morals, the conscious refusal to hide behind the veil of secrecy, and thus openly challenging established norms and values. As in the story of Lot (and the people of Sodom and Gomorrah), homosexual behaviour had become symptomatic of evil behaviour in general. It would inevitably lead to chaos and decay,  and therefore homosexuals were considered to be anti-social, and a threat to social order. Ayatollah Khomeini (1902-1989) alluded to this idea when saying that homosexuals were spreading the “stain of wickedness”, and should therefore be exterminated, since they were parasites and corruptors of the nation. Homosexuality was not only regarded as evil in itself, but also provided a convenient label for stigmatizing bad people in general. During this revolutionary period in Iran the term was used as a generic label, applied to persons who were considered, rightly or wrongly, to be criminals. It did not matter what they did exactly, it was enough to know they were anti-social and therefore evil. In this way, for example, political enemies were eliminated without any legal justification whatsoever. It is a historic tradition that in a situation of political, economic, and social instability, internal chaos will be blamed on outsiders and foreigners. And this made the homosexual a perfect scapegoat. (*3)

and therefore homosexuals were considered to be anti-social, and a threat to social order. Ayatollah Khomeini (1902-1989) alluded to this idea when saying that homosexuals were spreading the “stain of wickedness”, and should therefore be exterminated, since they were parasites and corruptors of the nation. Homosexuality was not only regarded as evil in itself, but also provided a convenient label for stigmatizing bad people in general. During this revolutionary period in Iran the term was used as a generic label, applied to persons who were considered, rightly or wrongly, to be criminals. It did not matter what they did exactly, it was enough to know they were anti-social and therefore evil. In this way, for example, political enemies were eliminated without any legal justification whatsoever. It is a historic tradition that in a situation of political, economic, and social instability, internal chaos will be blamed on outsiders and foreigners. And this made the homosexual a perfect scapegoat. (*3)

HOMOSEXUALITY AS EVIL: BIN LADEN AND TE LAWRENCE

The tradition of homosexuality being regarded as evil, and consequently being used to make bad people even worse than they already were, could also be observed after 9/11 when Bin Laden (1957-2011) himself was accused of effeminacy and homosexuality. Spy novelist John le Carré, for example, wrote, “The stylized television footage and photographs of this bin Laden suggest a man of homoerotic narcissism, and maybe we can draw a grain of hope from that. Posing with a Kalashnikov, attending a wedding or consulting a sacred text, he radiates with every self-adoring gesture an actor’s awareness of the lens. He has height, beauty, grace, intelligence and magnetism, all great attributes, unless you’re the world’s hottest fugitive and on the run, in which case they’re liabilities hard to disguise.” (*4) And Henry Porter of the Observer, adds TE in this picture, “Watching the al-Jazeera broadcast, we were all surely alert to the subliminal messages in the deceptive modesty of his glances, and to his neurotic effeminacy and self-love. It brought to mind the sexual ambivalence of T.E Lawrence who suggested … that truly dangerous men allow themselves to dream during daylight and then “act their dreams with their eyes open”.” (*5)

The tradition of homosexuality being regarded as evil, and consequently being used to make bad people even worse than they already were, could also be observed after 9/11 when Bin Laden (1957-2011) himself was accused of effeminacy and homosexuality. Spy novelist John le Carré, for example, wrote, “The stylized television footage and photographs of this bin Laden suggest a man of homoerotic narcissism, and maybe we can draw a grain of hope from that. Posing with a Kalashnikov, attending a wedding or consulting a sacred text, he radiates with every self-adoring gesture an actor’s awareness of the lens. He has height, beauty, grace, intelligence and magnetism, all great attributes, unless you’re the world’s hottest fugitive and on the run, in which case they’re liabilities hard to disguise.” (*4) And Henry Porter of the Observer, adds TE in this picture, “Watching the al-Jazeera broadcast, we were all surely alert to the subliminal messages in the deceptive modesty of his glances, and to his neurotic effeminacy and self-love. It brought to mind the sexual ambivalence of T.E Lawrence who suggested … that truly dangerous men allow themselves to dream during daylight and then “act their dreams with their eyes open”.” (*5)

These statements show that the label “homosexuality” (and nowadays “gay”) is closely connected with stereotyped images of predatory, abusive, and psychologically disturbed people, thus making a “homosexual” into someone you would definitely not take home and introduce to your mother, since he “hangs round the school gates with the drug pushers and paedophiles waiting, along with the bogeyman, to steal the souls of innocent children.” (*6) And for some people TE is one of them. Ilana Mercer, a conservative blogger who is fiercely anti-Arab and anti-Muslim, for example, speaks of “Lawrence‘s whimsical writings”, of “Lawrence’s Arabian Nights inspired oeuvre” and of Seven Pillars being “a veritable mirage of lies”. She blames TE for being responsible for the foundation of Arab unity, which according to her was only based on “the romantic hallucinations of a British homosexual”. It is because of his homosexuality that we are now saddled with these “decadent” Arabs. “Lawrence’s personal habits were not mere peccadilloes, as the personal and the political were one to him. His bizarre psychosexual identification with the Arabs was the root of his political beliefs.” (*7)

These statements show that the label “homosexuality” (and nowadays “gay”) is closely connected with stereotyped images of predatory, abusive, and psychologically disturbed people, thus making a “homosexual” into someone you would definitely not take home and introduce to your mother, since he “hangs round the school gates with the drug pushers and paedophiles waiting, along with the bogeyman, to steal the souls of innocent children.” (*6) And for some people TE is one of them. Ilana Mercer, a conservative blogger who is fiercely anti-Arab and anti-Muslim, for example, speaks of “Lawrence‘s whimsical writings”, of “Lawrence’s Arabian Nights inspired oeuvre” and of Seven Pillars being “a veritable mirage of lies”. She blames TE for being responsible for the foundation of Arab unity, which according to her was only based on “the romantic hallucinations of a British homosexual”. It is because of his homosexuality that we are now saddled with these “decadent” Arabs. “Lawrence’s personal habits were not mere peccadilloes, as the personal and the political were one to him. His bizarre psychosexual identification with the Arabs was the root of his political beliefs.” (*7)

HOMOSEXUALITY AS EVIL: THE ENGLAND OF TE’S TIME

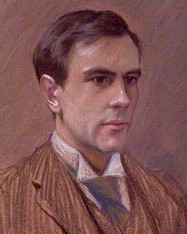

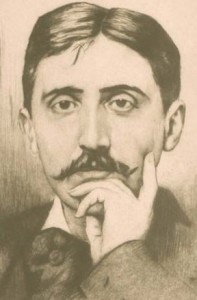

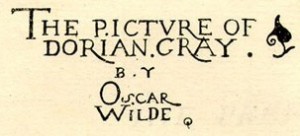

In TE’s lifetime homosexual acts were a criminal offence. If proof of penetration was provided, “buggery” was punished by penal servitude for a minimum of ten years up to life. Other homosexual acts, being acts of “gross indecency”, were punished by up to two years imprisonment with hard labour, whether they were in public or in private. (*8) The prosecution and conviction of Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) in 1895, and other homosexual scandals during the following decade, created a public image of the homosexual as “a corruptor of youth”. The danger of unregulated male lust and the general moral decadence of such behaviour, made homosexuality into a social evil which would only bring moral decline. It was even worse than just a contagious social disease, since contemporary medical opinion considered it to be an illness bordering on insanity.

In TE’s lifetime homosexual acts were a criminal offence. If proof of penetration was provided, “buggery” was punished by penal servitude for a minimum of ten years up to life. Other homosexual acts, being acts of “gross indecency”, were punished by up to two years imprisonment with hard labour, whether they were in public or in private. (*8) The prosecution and conviction of Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) in 1895, and other homosexual scandals during the following decade, created a public image of the homosexual as “a corruptor of youth”. The danger of unregulated male lust and the general moral decadence of such behaviour, made homosexuality into a social evil which would only bring moral decline. It was even worse than just a contagious social disease, since contemporary medical opinion considered it to be an illness bordering on insanity.  The days of intimate (often chaste) male friendships were over, and were replaced by an age of guilt and suspicion. If accused of homosexuality, a man in public life fled the country or killed himself.

The days of intimate (often chaste) male friendships were over, and were replaced by an age of guilt and suspicion. If accused of homosexuality, a man in public life fled the country or killed himself.

Typical of the period was the outraged reaction of the father of the poet John Betjeman (1906-1984), when he found out that his son had been corresponding with Wilde’s friend, Lord Alfred Douglas (1870-1945). “He’s a bugger. Do you know what buggers are? Buggers are two men who work themselves up into such a state of mutual admiration that one puts his piss-pipe up the other one’s arse. What do you think of that?” And of course I felt absolutely sick, and shattered.” (*9) But this was nothing compared with the violent reaction of the father of writer Beverley Nichols (1889-1983), after he found out that his son had been reading Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). “He seemed to choke. The purple deepened on his fat cheeks. He turned to me with an expression of such murderous hate that I stepped towards the wall. “You filthy little bastard!” he screamed … “Don’t you dare speak to me … you … you scum!” He hurled the book at my head … he struck me across the mouth. “Now … you pretty little bastard … you pretty little boy, watch me!” My father opened the book, very slowly, cleared his throat, and spat on the title page. Having spat once, he spat again; the action appeared to stimulate him.  Soon his chin was covered with saliva. Then, with a swift animal gesture, he lifted the book to his mouth, closed his teeth over some of the pages, and began tearing them to shreds … I could conceive no crime that could possibly cause any man’s name to be so hated (and asked) “What did Wilde do?” “What did he do?” He shook his head; the crime was too terrible to pass his lips. “Oh, my son … my son!” he groaned. And sinking on to the bed, he burst into tears.” The next morning his father threatened: “If ever I catch you reading a book by that man again, or if ever I so much as hear you mention his name …. I’ll cut your liver out.” The name of the crime he wrote down on a paper, because it was “unfit for a decent man to say”. It said “illum crimen horrible quod non nominandum est.” (“this horrible crime that dare not speak its name”) (*10)

Soon his chin was covered with saliva. Then, with a swift animal gesture, he lifted the book to his mouth, closed his teeth over some of the pages, and began tearing them to shreds … I could conceive no crime that could possibly cause any man’s name to be so hated (and asked) “What did Wilde do?” “What did he do?” He shook his head; the crime was too terrible to pass his lips. “Oh, my son … my son!” he groaned. And sinking on to the bed, he burst into tears.” The next morning his father threatened: “If ever I catch you reading a book by that man again, or if ever I so much as hear you mention his name …. I’ll cut your liver out.” The name of the crime he wrote down on a paper, because it was “unfit for a decent man to say”. It said “illum crimen horrible quod non nominandum est.” (“this horrible crime that dare not speak its name”) (*10)

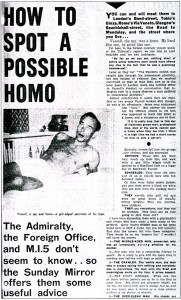

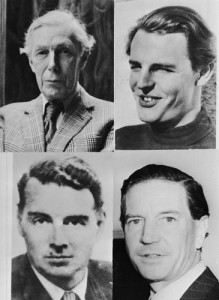

After the Second World War not much changed in regard to the attitude towards homosexuality. Homosexuals were still regarded as an alien class of humans, diabolical and separate from normal people. Politicians warned the public about the “insidious poisoning of Britain’s moral state” by juvenile crime and adultery, but in particular by “the vices of Sodom and Gomorrah”. To stop this plague, police agent-provocateurs were sent out to entrap homosexuals through solicitation. The Metropolitan Police even formed a special division solely to patrol public urinals, and consequently the number of prosecutions for homosexual offences skyrocketed. Even powerful and famous men (actors, politicians and lords) were paraded as examples in the press. In May 1952 The Sunday Pictorial devoted a full-page feature to help their readers recognize these “evil men”, and in 1961 it helpfully explained “How to Spot a Homo”. Readers could discern such a person by his sedate tweed jacket, suede shoes and pipe, or alternately by his telltale effeminate manner and mincing steps. These exposés reflected the anxieties born of the paradox that homosexuals, forced to live a double life, proved to be quite successful at it. They were considered to be the worst of the worst, and their lying and manipulating way of life made them even more dangerous. This belief was only confirmed by the case of the communist spies of “The Cambridge Four” (Philby, MacLean, Burgess and Blunt), which became public knowledge from 1956 onwards. (*11)

It was in this atmosphere that family, friends, and colleagues of TE were suddenly confronted with public accusations of TE being a homosexual. It is understandable therefore, that they were extremely disturbed and angered by this, since it was unimaginable to them that he was an evil person who belonged in jail. Corporal Jack Easton (1899-1990), who served with TE in the RAF in India (1927-1929), wrote the following to me when he was 90 years old: “Lawrence was a great, clean-living man and certainly not homosexual. I would stake my life that he was not a homosexual, but he has passed on, and is not here to defend himself, but I also would like to say that whoever said he was a homosexual, to me (it) is quite clear that they are homosexual themselves, and is trying to make excuses to say they are not, but nothing would make me say they are not when running down such a great man. I am sorry to say that no one has said he was a homosexual to me, as I certainly would let them know my feelings about Lawrence.” (*12)

POLITICAL ENEMIES

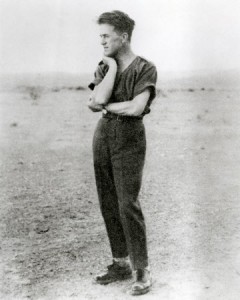

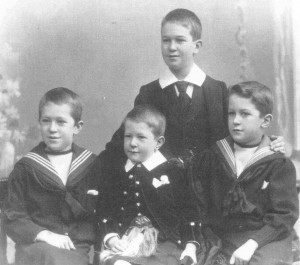

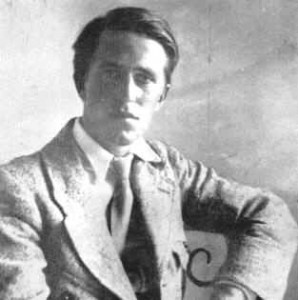

Rumours about TE’s supposed homosexuality already started during his lifetime. They came from people who resented his influence and reputation, and more particularly from the political and military enemies he made during the Arab Revolt and its political aftermath. TE was discredited for exaggerating his exploits, for his love of publicity and social eccentricity, and for his appalling and ill-mannered behaviour. An early example of the irritation his behaviour created is given by Lieutenant-Colonel Cyril Wilson (1873-1938), the British representative in Jeddah, in 1916. “Lawrence wants kicking and kicking hard at that, then he would improve. I look on him as a bumptious young ass who spoils his undoubted knowledge of Syrian Arabs etc. by making himself out to be the only authority on war, engineering, HM’s ships and everything else. He put every single person’s back up I’ve met from the Admiral down to the most junior fellow on the Red Sea.” (*13)  But the charge of homosexuality was not publicly expressed during his lifetime and even for a long time afterwards, probably to prevent cases of libel. Gossip about it, however could be found in private correspondences and club talk.

But the charge of homosexuality was not publicly expressed during his lifetime and even for a long time afterwards, probably to prevent cases of libel. Gossip about it, however could be found in private correspondences and club talk.

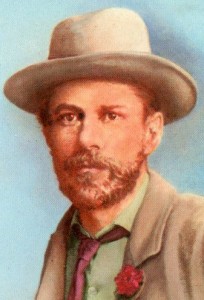

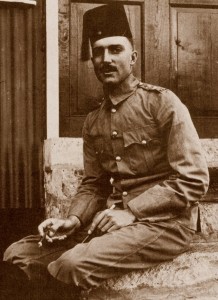

One of the groups who opposed TE’s political views on the Middle East, and felt threatened by his influence, was the so-called “Mesopotamian faction”, who wanted to keep Iraq as a British colonial possession. Among them was Colonel Arnold Wilson (1884-1940), who had been Acting Chief Political Officer in Mesopotamia during the war. (*14) Wilson’s ambitions of becoming the next High Commissioner of Iraq were shattered by the removal of British administration, Feisal becoming King of Iraq in 1921. This was a consequence of the politics of the Colonial Office, headed by Churchill and assisted in Middle East affairs by TE. Wilson felt he had been singled out by him as being responsible for the things that had gone wrong in Iraq, something for which he never forgave him. Afterwards he never missed a chance to denigrate TE and his achievements. After reading Seven Pillars, he said “I dislike the man and hate the matter. The first three pages are sickening and go far to prove what, from his beardlessness, his love of dressing & being photographed in long clothes, & from other signs & from conversation I long suspected – namely that homosexual practices are  Lawrence’s weakness – & the reason for his sojourn in the RAF & the Tankcorps.” (*15) It is not surprising therefore that when he was asked to review TE’s Revolt in the Desert (1927) and With Lawrence in Arabia (1924) by Lowell Thomas for The Journal of the Central Asian Society, he made the most of it. TE’s book is described as “a gratuitous parade of the author’s amiable eccentricities, couched in the language of the private schoolboy.” (*16) With this review of 1927 Wilson became the first to publicly refer to TE’s suspicious interest in the “unmentionable”, although still rather implicitly. “”The bird of Minerva”, wrote Landor, “flies low and picks up its food under hedges.” Lawrence’s hermaphrodite deity flies lower than Landor’s bird, and seems to have a preference for the cesspool, but we must be grateful to be spared, in this edition, more detailed references to a vice which Semitic races are by no means prone. To most English readers his Epipsychidion on this subject will be incomprehensible, to the remainder, unwelcome.” (*17) TE was not bothered in the least by Wilson roaring “like a bull from Basham”. (*18) He understood the political rancour behind “garbage mongering” of this sort, since Wilson had been in his way and therefore must have felt he was harmed greatly. (*19)

Lawrence’s weakness – & the reason for his sojourn in the RAF & the Tankcorps.” (*15) It is not surprising therefore that when he was asked to review TE’s Revolt in the Desert (1927) and With Lawrence in Arabia (1924) by Lowell Thomas for The Journal of the Central Asian Society, he made the most of it. TE’s book is described as “a gratuitous parade of the author’s amiable eccentricities, couched in the language of the private schoolboy.” (*16) With this review of 1927 Wilson became the first to publicly refer to TE’s suspicious interest in the “unmentionable”, although still rather implicitly. “”The bird of Minerva”, wrote Landor, “flies low and picks up its food under hedges.” Lawrence’s hermaphrodite deity flies lower than Landor’s bird, and seems to have a preference for the cesspool, but we must be grateful to be spared, in this edition, more detailed references to a vice which Semitic races are by no means prone. To most English readers his Epipsychidion on this subject will be incomprehensible, to the remainder, unwelcome.” (*17) TE was not bothered in the least by Wilson roaring “like a bull from Basham”. (*18) He understood the political rancour behind “garbage mongering” of this sort, since Wilson had been in his way and therefore must have felt he was harmed greatly. (*19)

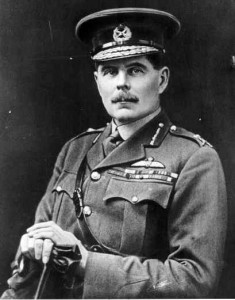

More political enemies of TE could be found in both the India Office and the Foreign Office. They were irritated by what they regarded as irresponsible behaviour during The Paris Peace Conference in 1919, and felt he had influenced Churchill in transferring Middle East affairs from them to the Colonial Office in 1921. For example, Field Marshall Sir Claude Jacob (1863-1948), secretary of the Military Department of the India Office, said, “I look on Lawrence as a fraud, and I am wondering when the bubble will burst.” (*20) An opinion that was shared by Sir Arthur Hirtzel (1870-1937), Secretary of the Political Department of the India Office, who said, “I don’t think I could have brought myself to work with Lawrence, who is as crooked as they make them. (…) He is rather like an overgrown schoolboy – full of wild “stunts”.” (*21) Finally, TE also made enemies with some French politicians and military, who blamed him for the harm he had done to their colonial ambitions in the Middle East. Colonel Edouard Brémond (1868-1948), for example, who served at the Military Mission in Jeddah (1916-1917), wrote of the suspicions that existed regarding TE, since “he was always strictly shaven in a country where the lack of a beard gave rise to suspicions which he was not spared.” (*22)

ENEMIES IN THE MILITARY

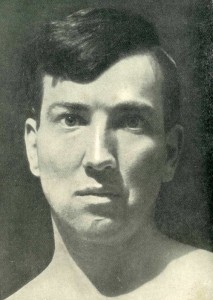

In England there were angry army officers too, who felt that TE had unduly grabbed most of the post-war limelight. In their eyes he had distanced himself from his proper place in society, through his unconventional and eccentric behaviour, even enlisting in the ranks, when a Colonel! When asked about TE, they remarked, “but of course, he was a homosexual.” One of the officers who criticized TE had served with him during the Arab Revolt. Major (later Lieutenant-Colonel) Charles Vickery (1881-1951) worked at the Arab Bureau (1916) and was artillery officer of the British Military Mission in the Hejaz from January to March 1917. From the moment they met, there was an immediate tension between them. TE regarded Vickery as a threat because of his status, being older and of higher rank, and also having a fluent knowledge of Arabic and a far greater military experience, even having served in desert warfare before. (*23) Vickery on his side condemned TE openly as “a braggart and visionary”, and considered him to be “military incompetent”. In his eyes, TE’s political approach to the Arab movement was “absurd”, and the Arab campaign he regarded as “professional suicide”. According to TE, “(Vickery) was too worldly to like the Arab revolt – indeed, no one but an enthusiast could have seen the ideal that lay behind its unpleasantness and puerilities – and the cold-blooded making use of an enthusiasm (my fashion) was equally beyond his understanding.” What made matters worse between them, was Vickery’s superior, colonialist and condescending attitude towards the Arabs, and his drinking, even becoming “a regal boon-companion”. (*24) TE was worried that this disrespectful and cynical attitude of Vickery would become a threat to his position, since he risked the contempt of the Arabs.  According to some biographers, TE sought every opportunity to humiliate and undermine his opponent in the eyes of Feisal’s troops, making his life impossible and working secretly to have him transferred to another front. (*25)

According to some biographers, TE sought every opportunity to humiliate and undermine his opponent in the eyes of Feisal’s troops, making his life impossible and working secretly to have him transferred to another front. (*25)

After the war Vickery was very hostile towards TE, spreading gossip around that he was a homosexual. According to Vickery, it explained TE’s ease in dealing with Feisal and the Arabs, since “The whole community is infected and saturated with vices of which nature abominates the idea”. (*26) In a conversation with the sculptress Lady Scott in February 1921, Vickery told her “the most hair-raising stories” about TE. “Says that it is common knowledge that he is a “royal mistress”, that that is the reason you never hear him spoken of in Arabia. When V referred to Hussain to him once, he replied “Don’t talk about that boy to me”. Once a rather beautiful young Arab came to him for a passport to Egypt and said he could pay, and produced a slab of gold as big as two man’s hands and said “That is the price of a night with Faisal” and so on. Countless tales! Well, well.” (*27)

HOMOSEXUALITY IN LAWRENCE BY HIS FRIENDS

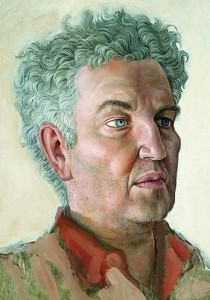

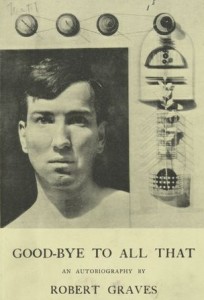

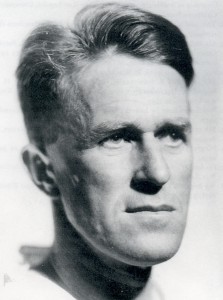

The first public reactions towards accusations of homosexuality were made in TE Lawrence By His Friends (published in May 1937). In this book of recollections edited by TE’s youngest brother Arnold Lawrence (1900-1991), two authors denied the rumours. Lowell Thomas (1892-1981), the man who stood at the basis of all the publicity about the “Uncrowned King of Arabia”, was very clear about these accusations. “There is one bit of false witness against Lawrence that I particularly want to nail. That is the charge spread by certain of his enemies that he was homosexual. In answer to this stupid canard I can say in the first place that anybody who has met thousands of men of all sorts and conditions can recognize a homosexual. If one has any prolonged contact with pathologues they are bound to give themselves away sooner or later by a gesture, a phrase, an inflection, a peculiar fashion of enunciating the sibilants. I have met all sorts and conditions, including several whose endocrine imbalance afflicted them with a sexual inversion. Furthermore, my father is a physician. I passed many hours, weeks, months in Lawrence’s company and never discerned in him the slightest indicia of the homosexual. But you don’t have to take my word for it.” (*28) The other person to deal with the subject in Friends was Leonard Woolley (1880-1960), a famous archaeologist who knew TE from the Carchemish excavations (1912-1914), the Sinai desert survey (1913) and his intelligence work in Cairo (1914-1915).

The first public reactions towards accusations of homosexuality were made in TE Lawrence By His Friends (published in May 1937). In this book of recollections edited by TE’s youngest brother Arnold Lawrence (1900-1991), two authors denied the rumours. Lowell Thomas (1892-1981), the man who stood at the basis of all the publicity about the “Uncrowned King of Arabia”, was very clear about these accusations. “There is one bit of false witness against Lawrence that I particularly want to nail. That is the charge spread by certain of his enemies that he was homosexual. In answer to this stupid canard I can say in the first place that anybody who has met thousands of men of all sorts and conditions can recognize a homosexual. If one has any prolonged contact with pathologues they are bound to give themselves away sooner or later by a gesture, a phrase, an inflection, a peculiar fashion of enunciating the sibilants. I have met all sorts and conditions, including several whose endocrine imbalance afflicted them with a sexual inversion. Furthermore, my father is a physician. I passed many hours, weeks, months in Lawrence’s company and never discerned in him the slightest indicia of the homosexual. But you don’t have to take my word for it.” (*28) The other person to deal with the subject in Friends was Leonard Woolley (1880-1960), a famous archaeologist who knew TE from the Carchemish excavations (1912-1914), the Sinai desert survey (1913) and his intelligence work in Cairo (1914-1915).  He starts his article in Friends by describing TE’s relationship with Dahum (1896-1918). Woolley states that the Arabs “were tolerantly scandalized by the friendship” of this Englishman of 24 and this handsome Arab boy of 15. Particularly after Dahum came to live with TE, and posed naked as a model for a gargoyle which TE was carving for the roof of their house. “The scandal about Lawrence was widely spread and firmly believed. The charge was quite unfounded. Lawrence had in his make-up a very strong vein of sentiment, but he was in no sense a pervert; in fact, he had a remarkably clean mind. He was tolerant, thanks to his classical reading, and Greek homosexuality interested him, but in a detached way, and the interest was not morbid but perfectly serious. I never heard him make a smutty remark and am sure that he would have objected to one if it had been made for his benefit; but he would describe Arab abnormalities baldly and with a certain sardonic humour. He knew quite well what the Arabs said about himself and Dahoum and so far from resenting it was amused, and I think he courted misunderstanding rather than tried to avoid it; it appealed to his sense of humour, which was broad and schoolboyish. He liked to shock.” (*29) A remarkable denial, especially since it gives information which would make some people even more suspicious of TE’s homosexuality. It is no surprise therefore, that friends, admirers and even biographers of TE were rather unhappy with Woolley’s statements about TE being “devoted” to an Arab boy who was “beautifully built and remarkably handsome”, about living together and letting the boy pose naked, and about being interested in Greek homosexuality and having knowledge of “Arab abnormalities”. (*30)

He starts his article in Friends by describing TE’s relationship with Dahum (1896-1918). Woolley states that the Arabs “were tolerantly scandalized by the friendship” of this Englishman of 24 and this handsome Arab boy of 15. Particularly after Dahum came to live with TE, and posed naked as a model for a gargoyle which TE was carving for the roof of their house. “The scandal about Lawrence was widely spread and firmly believed. The charge was quite unfounded. Lawrence had in his make-up a very strong vein of sentiment, but he was in no sense a pervert; in fact, he had a remarkably clean mind. He was tolerant, thanks to his classical reading, and Greek homosexuality interested him, but in a detached way, and the interest was not morbid but perfectly serious. I never heard him make a smutty remark and am sure that he would have objected to one if it had been made for his benefit; but he would describe Arab abnormalities baldly and with a certain sardonic humour. He knew quite well what the Arabs said about himself and Dahoum and so far from resenting it was amused, and I think he courted misunderstanding rather than tried to avoid it; it appealed to his sense of humour, which was broad and schoolboyish. He liked to shock.” (*29) A remarkable denial, especially since it gives information which would make some people even more suspicious of TE’s homosexuality. It is no surprise therefore, that friends, admirers and even biographers of TE were rather unhappy with Woolley’s statements about TE being “devoted” to an Arab boy who was “beautifully built and remarkably handsome”, about living together and letting the boy pose naked, and about being interested in Greek homosexuality and having knowledge of “Arab abnormalities”. (*30)

But it seems that the publication of these defensive reactions by Thomas and Woolley were well intended by the editor of the book, TE’s brother Arnold. And it is even possible that he asked them to include it in their respective articles for Friends, particularly since he himself decided to write an article for the book, in which he denied the rumours that TE was homosexual. In the article, Arnold states that TE’s hatred of women was just a legend and had no foundation in reality, remembering his long standing friendships with women. TE regarded the marriage of his friends with an envious tenderness, revealing a longing for similar companionship. Another legend he contradicts was the accusation that TE’s relationships with young men led to sodomy or inclinations thereto. According to him, these relationships were only fostered by TE’s missionary spirit, in which he always tried to develop the capabilities of those with whom he came into contact. The men involved always denied and even fiercely resented any suggestion of homosexuality being ascribed to their relationships with TE. The emotional friendship TE describes in the dedicatory poem of the Seven Pillars, was in Arnold’s eyes, only a longing for companionship caused by the confined loneliness of a European’s life in the Near East, and nothing more. The poem was mainly a literary exercise (influenced by English verse of the nineties) intended to recall not only the dead friend, but also the cast-off self of his own youth. Finally, Arnold said, his brother had stated in his letters with the utmost clarity that he had very rarely felt physical inclination towards any person, and had lived in complete celibacy toward both sexes.

But it seems that the publication of these defensive reactions by Thomas and Woolley were well intended by the editor of the book, TE’s brother Arnold. And it is even possible that he asked them to include it in their respective articles for Friends, particularly since he himself decided to write an article for the book, in which he denied the rumours that TE was homosexual. In the article, Arnold states that TE’s hatred of women was just a legend and had no foundation in reality, remembering his long standing friendships with women. TE regarded the marriage of his friends with an envious tenderness, revealing a longing for similar companionship. Another legend he contradicts was the accusation that TE’s relationships with young men led to sodomy or inclinations thereto. According to him, these relationships were only fostered by TE’s missionary spirit, in which he always tried to develop the capabilities of those with whom he came into contact. The men involved always denied and even fiercely resented any suggestion of homosexuality being ascribed to their relationships with TE. The emotional friendship TE describes in the dedicatory poem of the Seven Pillars, was in Arnold’s eyes, only a longing for companionship caused by the confined loneliness of a European’s life in the Near East, and nothing more. The poem was mainly a literary exercise (influenced by English verse of the nineties) intended to recall not only the dead friend, but also the cast-off self of his own youth. Finally, Arnold said, his brother had stated in his letters with the utmost clarity that he had very rarely felt physical inclination towards any person, and had lived in complete celibacy toward both sexes.

In the end Arnold decided against publication of his defence in Friends, probably because he came to feel (or was advised), that the arguments employed were weak. A loyal fraternal reaction might have done little to convince most readers, while the arguments could have added fuel to the fire, and only have led to more suspicions. Still he chose to include the defences by Thomas and Woolley, since a response by two publicly well-known people, with a reputation in their respective fields, might be taken more seriously. Both the denials of TE’s homosexuality as published in Friends and the unpublished one by his brother are very interesting, since they give us the first impression of the arguments which TE’s friends and biographers would later use to counter accusations of homosexuality. The question that still puzzles me however, is why Arnold felt the need to go public with it? What happened in the period after TE’s death in 1935 that caused his brother to come to his defence in public? Were the gossip and rumours so outrageous that he felt he just had to protect the reputation of his family, of intimate friends and of the people who had worked and lived with TE in the military, from being harmed? And since getting it out in the open could have just as easily ended up being counter-productive, was it worth the risk? (*31)

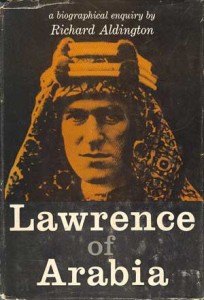

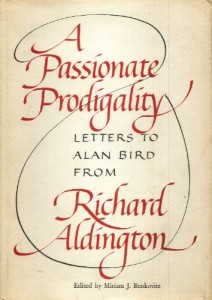

RICHARD ALDINGTON AND HIS HATRED FOR TE

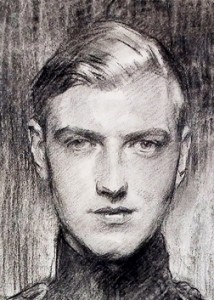

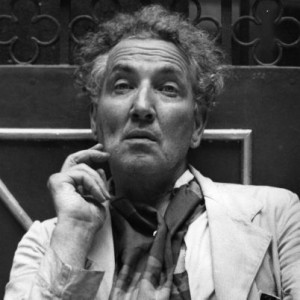

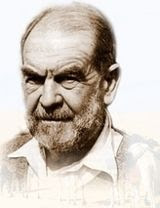

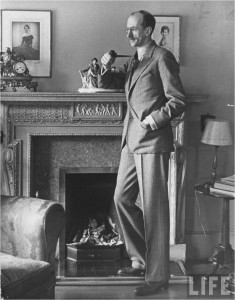

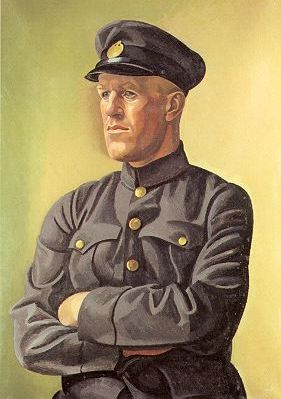

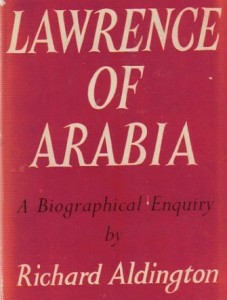

The first biographer to publicly draw attention to TE’s illegitimacy and “sympathy for homosexuality” was Richard Aldington (1892-1962) (*32) in his book Lawrence of Arabia: a Biographical Enquiry (1955). Aldington and TE had much in common. While Aldington’s father was gentle and easy, his mother (a writer) was strong-willed and turbulent, and a typical “will-to-power mother” whom he actively disliked and even hated. (*33) Both translated the Greek poet Meleager of Gadara (1st century BC), and while TE abandoned a translation of Sturly (1924) by the French writer Pierre Custot, Aldington finished it, leaving TE the task of writing the blurb on the dust jacket. The two also shared horrifying and disturbing war experiences and wrote books to deal with them. According to Aldington, he was the one who really suffered during the war, while TE had a very easy time. TE’s book Revolt In The Desert was a success (as was Seven Pillars after his death), but Aldington’s Death Of A Hero (1929) was not. Aldington was of the opinion that he had made genuine achievements and had done first-rate work in literature (translating from Italian, Provencal, Greek and French, editing an anthology of English-language poetry, etc.), while he considered TE’s literary reputation to be largely inflated. All in all TE came to represent everything Aldington hated. For him TE’s popularity was undeserved, since he was just “a phoney, a liar and a praiser of pederasts”. (*34) TE’s enormous public success confronted Aldington with his own failure to fulfil his ambitions of being successful, or at least of making a good living at the things he was good at. It made him desperate to prove to the world that TE was an habitual poseur and liar, and even a criminal who belonged in jail. He might have hoped that everyone would see that they had been wrong about their “Arabian knight”, and that he would finally and deservedly become a successful writer.

The first biographer to publicly draw attention to TE’s illegitimacy and “sympathy for homosexuality” was Richard Aldington (1892-1962) (*32) in his book Lawrence of Arabia: a Biographical Enquiry (1955). Aldington and TE had much in common. While Aldington’s father was gentle and easy, his mother (a writer) was strong-willed and turbulent, and a typical “will-to-power mother” whom he actively disliked and even hated. (*33) Both translated the Greek poet Meleager of Gadara (1st century BC), and while TE abandoned a translation of Sturly (1924) by the French writer Pierre Custot, Aldington finished it, leaving TE the task of writing the blurb on the dust jacket. The two also shared horrifying and disturbing war experiences and wrote books to deal with them. According to Aldington, he was the one who really suffered during the war, while TE had a very easy time. TE’s book Revolt In The Desert was a success (as was Seven Pillars after his death), but Aldington’s Death Of A Hero (1929) was not. Aldington was of the opinion that he had made genuine achievements and had done first-rate work in literature (translating from Italian, Provencal, Greek and French, editing an anthology of English-language poetry, etc.), while he considered TE’s literary reputation to be largely inflated. All in all TE came to represent everything Aldington hated. For him TE’s popularity was undeserved, since he was just “a phoney, a liar and a praiser of pederasts”. (*34) TE’s enormous public success confronted Aldington with his own failure to fulfil his ambitions of being successful, or at least of making a good living at the things he was good at. It made him desperate to prove to the world that TE was an habitual poseur and liar, and even a criminal who belonged in jail. He might have hoped that everyone would see that they had been wrong about their “Arabian knight”, and that he would finally and deservedly become a successful writer.  Aldington could have produced a masterpiece, since it was the first book which looked with a critical eye at the myth of Lawrence of Arabia. But unfortunately he was so full of hatred, jealousy and prejudice about TE, mistrusting everything “the world’s phoney” said or did, that he overreacted and produced a biography which was mostly contemptuous and debunking. And paradoxically he was not taken seriously himself again. (*35)

Aldington could have produced a masterpiece, since it was the first book which looked with a critical eye at the myth of Lawrence of Arabia. But unfortunately he was so full of hatred, jealousy and prejudice about TE, mistrusting everything “the world’s phoney” said or did, that he overreacted and produced a biography which was mostly contemptuous and debunking. And paradoxically he was not taken seriously himself again. (*35)

Originally Aldington intended to write only a brief chapter on TE’s sex life, in which he would point out the lack of love affairs and the lack of evidence regarding his sex habits. His plan was to bring together a number of his most striking pronouncements on sex, from which the reader could form his own judgement. But during his research and writing, his hatred and prejudices took over, and more and more he wanted to prove that TE was a homosexual, and therefore an untrustworthy, criminal and evil person. Aldington started collecting TE’s “anti-hetero and pro-homo statements”, from which he concluded that “The praise of homosexuality in 7P is so flagrant (*36), the doing dirt on women so whole-hearted throughout his life (*37), that there can be no doubt where his interests lay.” (*38) In his private correspondence he called TE a “dreary little bugger”, who “belonged to the great international trade union of sods”, and showed “that peculiar mixture of insolence and lying so typical of pederasts.”(*39) Like many of his contemporaries, Aldington was rather prejudiced about homosexuality. (*40) He called it a sexual habit, which was “un-English” (*41), but had suddenly become fashionable, with the result that “it is practically impossible to succeed in the upper class unless one is a bugger.” (*42) He resented “this sickly homosexuality”, since “eager-eyed Sodomites” like TE and the writer Norman Douglas (1868-1952), both “heroes of the homosexuals & themselves particularly impudent practitioners & preachers” (*43), had made affection between normal men suspect, and with it Aldington’s own bond with men and his feelings toward them during the war. “Friendships between soldiers during the war were a real and beautiful and unique relationship which has now entirely vanished, at least from Western Europe. …. there was nothing sodomitical in these friendships … It was just a human relation, a comradeship, an undemonstrative exchange of sympathies between ordinary men racked to extremity under a great common strain in a great common danger. There was nothing dramatic about it.” (*44) Still it seems that in his private life Aldington maintained rather amiable friendships with homosexuals, and seemed to resent homosexuality only when it appeared as a trait of an enemy. (*45)

Like many of his contemporaries, Aldington was rather prejudiced about homosexuality. (*40) He called it a sexual habit, which was “un-English” (*41), but had suddenly become fashionable, with the result that “it is practically impossible to succeed in the upper class unless one is a bugger.” (*42) He resented “this sickly homosexuality”, since “eager-eyed Sodomites” like TE and the writer Norman Douglas (1868-1952), both “heroes of the homosexuals & themselves particularly impudent practitioners & preachers” (*43), had made affection between normal men suspect, and with it Aldington’s own bond with men and his feelings toward them during the war. “Friendships between soldiers during the war were a real and beautiful and unique relationship which has now entirely vanished, at least from Western Europe. …. there was nothing sodomitical in these friendships … It was just a human relation, a comradeship, an undemonstrative exchange of sympathies between ordinary men racked to extremity under a great common strain in a great common danger. There was nothing dramatic about it.” (*44) Still it seems that in his private life Aldington maintained rather amiable friendships with homosexuals, and seemed to resent homosexuality only when it appeared as a trait of an enemy. (*45)

Although Aldington privately claimed he had “overwhelming proofs” of TE’s homosexuality (*46), the evidence which he brought forward in his biography was only circumstantial. The only claim he made was that TE’s sexual preferences were “anti-female and pro-male”. According to Aldington, TE had openly declared his hatred for women and his disgust for sex with them in his writings and showed disdain for heterosexual relations. On the other hand, his sympathy for homosexual relations was very clear, Seven Pillars being an outspoken “declaration of preference for homosexuality”. TE also had many friends who were homosexual, while his intimate friendships with men were “comparable in intensity to sexual love”. Aldington blamed the lack of evidence of actual homosexual behaviour on the fact that “relatives and friends are the last persons to hear of or to suspect homosexual practices”. (*47) The main reason for Aldington’s reserve in the book, was the fact that his publishers and lawyers had warned him of a possible libel prosecution by TE’s friends. He did not include, for example, information which related TE’s death to his homosexuality.

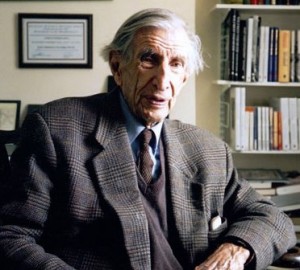

The head of Scotland Yard had told the writer Somerset Maugham (1874-1965) that TE’s death was no accident, but suicide. “He had been using Clouds Hill as a rendezvous with private soldiers, and almost openly, relying on his quasi-immunity as the “prince of Mecca”. Nothing was done while he was in the RAF, but within a few weeks after his discharge, the usual warrant was issued, and the usual inspector in plain clothes called to give the 24 hours’ warning to get out of England, or … TEL preferred suicide.” (*48) In this case the information was rather questionable, and Aldington was probably right not to use it. First of all, the source of the story, Somerset Maugham, was known as being an incorrigible gossip, who savoured homosexual scandal. Secondly, no official proof of any of this could be found, and knowing Aldington and his intentions, he must have done his best to find out if this rumour could be substantiated. (*49) Finally, it is very unlikely that people in high places (both enemies and friends of TE) would have allowed having a scandal on their hands, which would have shattered a national hero and with it Britain’s prestige. (*50)

The head of Scotland Yard had told the writer Somerset Maugham (1874-1965) that TE’s death was no accident, but suicide. “He had been using Clouds Hill as a rendezvous with private soldiers, and almost openly, relying on his quasi-immunity as the “prince of Mecca”. Nothing was done while he was in the RAF, but within a few weeks after his discharge, the usual warrant was issued, and the usual inspector in plain clothes called to give the 24 hours’ warning to get out of England, or … TEL preferred suicide.” (*48) In this case the information was rather questionable, and Aldington was probably right not to use it. First of all, the source of the story, Somerset Maugham, was known as being an incorrigible gossip, who savoured homosexual scandal. Secondly, no official proof of any of this could be found, and knowing Aldington and his intentions, he must have done his best to find out if this rumour could be substantiated. (*49) Finally, it is very unlikely that people in high places (both enemies and friends of TE) would have allowed having a scandal on their hands, which would have shattered a national hero and with it Britain’s prestige. (*50)

This article will be continued in the next post: “The Label “Homosexual” – 2nd Part: Defences”.

The notes for this article can be found in: “The Label “Homosexual” – 3d Part: Notes”.